- Introduction

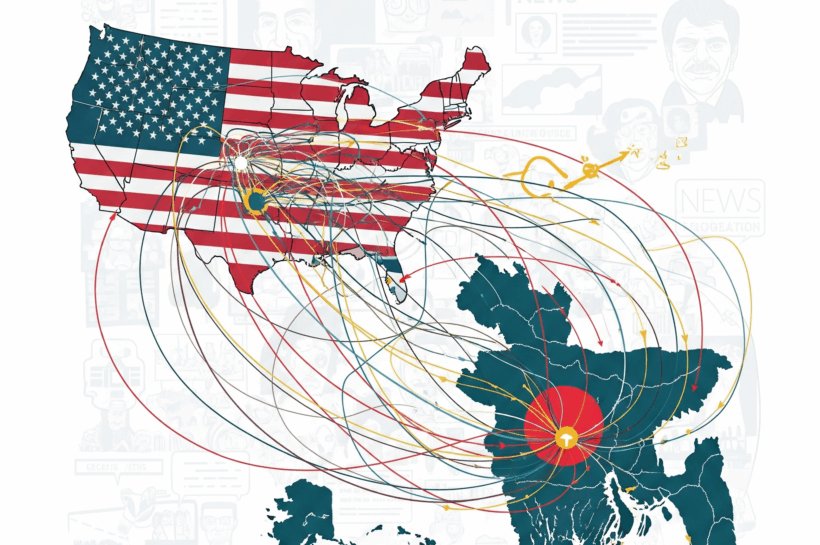

In July 2025, a confidential draft of the so-called U.S.-Bangladesh Agreement on Reciprocal Trade was leaked. At first glance, it appeared to be a bilateral deal to facilitate trade flows between the two countries. However, on closer inspection, the document revealed something far more consequential: a complex and far-reaching framework that, if ratified, would embed U.S. influence deep into Bangladesh’s economic, legal, and digital infrastructures. Drafted amid political instability and under an unelected interim government, this agreement must be understood not merely as a trade pact, but as a coercive tool of structural realignment: one that reorients Bangladesh’s legal, economic, and geopolitical frameworks to align with U.S. priorities, without public consultation or democratic mandate.

This paper offers a critical examination of the agreement, exploring its key provisions, underlying logic, and broader implications. It further contextualizes the agreement within a lineage of similarly coercive international arrangements and concludes with strategic recommendations for activists, policymakers, and civil society actors committed to protecting Bangladesh’s sovereignty.

1.1 Security Classification

- Marked CONFIDENTIAL, with “Modified Handling Authorized.”

- Declassification set for 4 years after enforcement/negotiation closure.

- Suggests it is either a draft or pre-ratification version.

- Legal effect is not yet public—yet expectations and timelines for Bangladeshi compliance are clear and immediate.

2. Critical Analysis of the Agreement

The agreement, sprawling across 21 pages, is organized into six major sections: taxation, non tariff barriers, digital trade and technology, rules of origin, commercial and national security

terms, and investment and services. While billed as reciprocal, the obligations it places on

Bangladesh far outweigh those asked of the United States.

2.1 Tariff & Non-Tariff Barriers

One of the most striking aspects of the draft agreement lies in its treatment of tariff and non-tariff

barriers. Bangladesh is effectively being asked to lower customs duties specifically on U.S. goods, potentially undermining the country’s ability to protect its local industries through strategic tariffs.

Even more troubling, however, is a clause that would require Bangladesh to accept approvals from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as automatically sufficient for the import of medical devices, pharmaceuticals, and agricultural and food products. In practical terms, this means that products certified by the U.S. regulatory system could bypass any scrutiny by Bangladeshi authorities.

The implications are profound: such a provision would amount to a wholesale surrender of regulatory sovereignty. It would give U.S. corporations a free pass into the Bangladeshi market, allowing them to operate under their own standards—regardless of whether those standards align with Bangladesh’s public health, safety, or environmental priorities.

2.2 Agricultural and Food Imports

The draft agreement also proposes sweeping changes to how Bangladesh handles agricultural and food imports—changes that would strip the country of its ability to independently regulate what its people consume. Under the proposed terms, Bangladesh would be required to accept U.S. Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) standards wholesale, without the option for additional inspections or safety testing at the border.

Codex Alimentarius Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) would be enforced as the default standard, further reducing Bangladesh’s capacity to implement context-specific health protections. Perhaps most alarming is the clause concerning genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and biotech foods: if a product is approved in the United States, it would automatically be legal in Bangladesh—with no local review or public input.

In the case of U.S. dairy, meat, poultry, and aquatic products, the agreement mandates that American health certificates alone would suffice for entry—effectively preventing Bangladeshi authorities from conducting their own assessments. This arrangement would open the floodgates to heavily processed and genetically modified foods, many of which may enter the market without proper labeling or public awareness. For a country that has long fought for food sovereignty, this provision amounts to an abdication of the right to decide what is safe, sustainable, and culturally acceptable for its people.

2.3 Digital Trade and Surveillance Tech

The chapter on digital trade reads less like a bilateral agreement and more like a how to manual for transplanting the U.S. surveillance capitalism playbook onto Bangladeshi soil. In black and white language, Bangladesh would be compelled to “harmonize” its cybersecurity laws with American norms—starting with the repeal of hard won traceability provisions and the scrapping of any rule that lets regulators demand encryption keys. In other words, the very tools Bangladeshi authorities use to audit big tech behavior at home would have to be dismantled so that U.S. firms can operate friction free.

The text then insists that Dhaka formally recognize the Global Cross Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) and Privacy Recognition for Processors (PRP) frameworks—both architected and stewarded in Washington. Once adopted, data generated in Bangladesh could legally shuttle across servers on multiple continents with only U.S. oversight, eviscerating any ambition the country has for data localization or stronger local privacy standards.

Finally, the pact pries open the coveted 6 GHz spectrum—prime real estate for next gen Wi Fi and 5G—and reserves first dibs for American technology vendors. Taken together, these measures would tether Bangladesh’s digital future to the commercial ambitions of Silicon Valley and Beltway lobbyists, while gutting the regulatory levers meant to protect citizens’ privacy, security, and sovereign control over national data infrastructure.

2.4 Labour and EPZ Reforms

On paper, the agreement’s provisions on labor rights and Export Processing Zone (EPZ) reforms appear progressive—perhaps even laudable. It calls for amendments to the Bangladesh Labour Act (BLA) that would lower the thresholds required for union registration, ease penalties for strikes, and extend full union rights to workers in EPZs, who have long been denied basic collective bargaining protections. The text also includes strong language against practices like blacklisting, retaliation, and forced labor.

But a deeper reading reveals a paradox. These demands are being championed by a country—namely, the United States—that has itself faced widespread criticism for the erosion of collective bargaining rights and the weakening of organized labor. From right-to-work laws to the systemic underfunding of the National Labor Relations Board, U.S. labor policy is hardly a model of worker empowerment. The agreement thus rings hollow: Washington is asking Bangladesh to uphold labor standards that it has failed to secure at home.

This contradiction raises unsettling questions about intent. Are these labor reforms being pushed out of genuine solidarity with Bangladeshi workers—or are they being weaponized as leverage to restructure industrial relations in a way that ultimately benefits foreign buyers and their supply chain efficiencies, while branding Bangladesh’s labor market as “ethical” for export advantage?

2.5 Environment, Fisheries, and Forestry

The environmental chapter of the agreement outlines a number of firm commitments that, at first glance, appear commendable. Bangladesh would pledge to crack down on illegal logging and wildlife trafficking, align itself with the WTO Fisheries Subsidies Agreement, and phase out environmentally harmful subsidies in the fisheries sector. These are, undeniably, important global priorities—and if enforced with sincerity and fairness, could contribute to a more sustainable future.

However, the asymmetry built into these obligations is hard to ignore. The burden of compliance falls squarely on Bangladesh, with little indication of reciprocal commitments from the United States. While Dhaka is expected to align its environmental and resource management policies with international—and, by implication, U.S.—standards, there is no corresponding requirement for the U.S. to adjust its own practices or provide tangible support for Bangladesh’s transition. This imbalance suggests that environmental protection, like other areas in the agreement, is being framed less as a shared responsibility and more as a checklist of conditions imposed on the weaker party. What could have been a platform for genuine climate cooperation instead risks becoming another mechanism for unequal power projection under the banner of sustainability.

2.6 Rules of Origins, Services, and Investment

The section on rules of origin, services, and investment reads like a corporate wishlist—one that places U.S. investors at the center of Bangladesh’s strategic sectors. Under the proposed terms, Bangladesh would be required to deregulate critical industries such as insurance, telecommunications, and energy, effectively removing long-standing protections meant to safeguard national development and public interest.

Notably, the agreement abolishes caps on foreign ownership in these sectors, allowing U.S. firms to take full control of local enterprises. It also guarantees streamlined investment approvals for American entities, along with the unrestricted repatriation of capital and profits—privileges that are rarely extended to Bangladeshi investors abroad.

The result is a glaring asymmetry. While Bangladesh opens up its economy with few guardrails, the agreement lacks any meaningful mechanisms to ensure reciprocity, technology transfer, or reinvestment in local development. This isn’t investment guided by shared prosperity—it’s a structural tilt in favor of capital-rich foreign actors, cementing a model of extractive globalization where Bangladesh remains a site of consumption and cheap labor, not of strategic growth or sovereign decision-making.

2.7 Geopolitical/Defence Implications

Perhaps the most consequential—and geopolitically loaded—section of the agreement concerns defense and strategic alignment. Under its terms, Bangladesh would be required to ban the use of LOGINK, a Chinese state-backed global logistics network, effectively signaling a break with Beijing’s expanding digital infrastructure footprint. Simultaneously, the agreement obliges Dhaka to ramp up purchases of U.S. military and civilian aviation equipment, as well as increase imports of American energy commodities such as LNG, soybeans, and wheat.

Beyond trade and procurement, the deal would also place Bangladesh under the jurisdiction of U.S. export controls—specifically the Export Administration Regulations (EAR)—a framework often used to block technology transfers to rival nations and enforce strategic compliance. Taken together, these provisions mark a sharp pivot away from Bangladesh’s historically non aligned foreign policy stance. By embedding itself within a U.S.-led security and economic architecture, Bangladesh risks compromising its diplomatic flexibility and inviting friction with key partners like China. The implications for national sovereignty are profound: rather than navigating multipolar alliances on its own terms, Bangladesh would be tethered to Washington’s geopolitical agenda—an alignment that may carry hidden costs well beyond the scope of this trade deal.

3. Summary: What the Agreement Actually Is

At its core, this agreement is not merely about trade. It is a sweeping, multi-sectoral realignment that reaches deep into the architecture of Bangladesh’s governance, economy, and foreign policy. Far from being a standard commercial accord, it functions as a strategic alignment pact—one that demands profound concessions without offering proportional returns.

Under its terms, Bangladesh is asked to relinquish key elements of its regulatory sovereignty across multiple domains: pharmaceuticals, digital governance, agriculture, and surveillance technologies. It must bind itself to Western-dominated frameworks like the Codex Alimentarius and WTO fisheries disciplines, even when those standards may not reflect local needs or realities.

Simultaneously, the agreement facilitates a dramatic expansion of U.S. corporate influence in critical sectors—energy, aviation, agriculture, insurance, and logistics—while dismantling long standing protections designed to foster domestic development. On the geopolitical front, it unmistakably tilts Bangladesh away from China, particularly in logistics and digital infrastructure, locking the country into a U.S.-centered orbit with few exit ramps.

Perhaps most revealing is what the agreement does not contain: there are no guarantees of duty free market access, no pledges of development assistance, and no commitments to debt relief. In essence, Bangladesh is being asked to restructure its economy, compromise its strategic autonomy, and absorb the consequences of alignment—without the benefits typically associated with such deep partnerships.

4. Comparative Historical Parallels

This agreement is not unprecedented. It falls within a pattern of coercive economic arrangements often pushed by powerful nations under the guise of liberal trade.

4.1 USMCA (United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement)

To understand the deeper structure of the proposed Bangladesh agreement, one need only look to the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA)—the successor to NAFTA—as a precedent. Like the current deal, USMCA was crafted to entrench U.S. corporate interests, especially in areas like intellectual property, pharmaceuticals, and digital trade. Both Canada and Mexico were compelled to harmonize their laws with U.S. standards—extending drug patent protections, tightening copyright enforcement, and scaling back the influence of state-owned enterprises.

Canada, for instance, was forced to open its tightly regulated dairy market to U.S. producers, a move that triggered widespread backlash from Canadian farmers. Mexico, under sustained U.S. pressure, had to overhaul its labor laws in ways that echo the reforms now being demanded of Bangladesh—lower union thresholds, new enforcement mechanisms, and a more liberalized labor environment conducive to multinational supply chains.

Yet there’s a crucial distinction. USMCA was the result of intense trilateral negotiations involving countries with significant economic weight and reciprocal market access. Canada and Mexico, though pressured, retained leverage by virtue of their integration into North American value chains. Bangladesh, by contrast, enters this negotiation with none of that clout. It has no comparable consumer market to offer in exchange, no strategic integration that binds U.S. stakeholders to compromise. The result is a one-sided bargain: structural concessions with little in the way of economic gain or negotiated balance. [USTR, 2020]

4.2 U.S.–Colombia Free Trade Agreement (2012)

The U.S.–Colombia Free Trade Agreement, enacted in 2012, offers another revealing parallel. As a condition for the deal, Colombia was required to implement far-reaching labor reforms, much like the stipulations now being placed before Bangladesh. Yet in practice, many of these labor protections remained under-enforced—highlighting the gap between paper commitments and real outcomes. Still, once the agreement was signed, Colombia became deeply embedded in U.S.-centric supply chains and increasingly reliant on U.S. financial flows.

The trade liberalization also led to a flood of U.S. agricultural imports, which undercut local producers and destabilized rural economies. Meanwhile, stringent U.S.-driven rules on intellectual property and pharmaceuticals curtailed Colombia’s ability to manufacture or import affordable generic medicines—raising serious public health concerns.

Despite these downsides, Colombia at least secured certain agricultural carve-outs and safeguards in its negotiations—something notably absent from the draft Bangladesh agreement. In effect, Bangladesh is being offered the same structural model—sweeping legal reforms, deep market exposure, and IP alignment—but with even fewer protections for its domestic industries and rural communities. [HRW, 2011]

4.3 Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) in Africa

Bangladesh’s draft investment provisions bear an uncanny resemblance to a troubling pattern seen across the Global South—most notably in Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) signed between several African nations and wealthier powers like the U.S., EU, and Canada. Countries such as Tanzania, Mozambique, and Ghana were lured into these treaties under the promise of increased foreign capital, but the reality often proved far more costly.

These BITs routinely granted foreign corporations sweeping investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) rights, enabling them to sue host governments in international arbitration tribunals for policies—whether environmental protections, labor regulations, or tax reforms—that might affect their “expected profits.” In essence, multinational companies gained veto power over sovereign legislation, without being bound by any obligation to invest in a way that supports local development or public welfare. Crucially, these treaties were almost never reciprocal. African firms received no meaningful access to Western markets or protections for their outbound investments. The arrangement was lopsided from the start.

The investment chapter in Bangladesh’s draft agreement follows the same playbook: it proposes wide-scale liberalization of foreign ownership and ease of capital extraction, but without enforcing checks, balances, or mutual benefits. It is a familiar trap—dressed in the language of development, but rigged in favor of those who already hold the capital, the legal muscle, and the global negotiating power. [South Centre, 2016]

4.4 IMF Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs)

The proposed agreement also echoes an earlier and deeply controversial chapter in global economic history: the era of IMF Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) from the 1980s through the early 2000s. While not framed as trade deals, these programs imposed sweeping economic reforms on countries in exchange for desperately needed loans—reforms that often dismantled public sectors and hollowed out social safety nets.

Under SAP conditionalities, governments were compelled to privatize health, education, and essential services, regardless of public need or access. Subsidies that supported farmers and local industries were slashed overnight, triggering widespread job losses, deepening poverty, and social unrest across much of the Global South. In the name of “efficiency” and “fiscal responsibility,” nations lost control over their own development trajectories.

What’s striking about the Bangladesh agreement is that it mirrors the logic of a structural adjustment program—yet without even offering the financial lifeline of a loan in return. It demands legislative, labor, and governance concessions reminiscent of the IMF’s most extractive terms, but frames them as the price of political legitimacy and elite continuity in a post-coup or post-crisis setting.

In effect, Bangladesh is being asked to undergo structural adjustment not to stave off default or economic collapse—but simply to buy its way into a Western-aligned political and economic order. [SAPRIN, 2004]

4.5 Australia–U.S. Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA)

The Australia–U.S. Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA) serves as yet another cautionary tale in the architecture of American trade diplomacy. As part of the deal, Australia agreed to dilute its pharmaceutical price controls—undermining a key pillar of its public health system. While U.S. exports to Australia soared in the years following the agreement, Australia’s own access to U.S. markets, particularly in agriculture, remained severely limited.

Critics pointed to the deal’s structural imbalance: it expanded U.S. corporate reach into Australia’s domestic policy space without offering reciprocal trade benefits. Most alarmingly, the agreement was seen as a retreat from national sovereignty in areas as sensitive as health care pricing and essential medicine access.

Yet the terms currently being proposed for Bangladesh go even further. They don’t just touch on public health—they encroach on food sovereignty, digital governance, and regulatory independence across a wide swath of economic sectors. Bangladesh is not simply being asked to open its markets—it is being asked to rewire its policy landscape in a way that relinquishes control over the very levers of self-determination. Compared to AUSFTA, this is not just a trade imbalance—it is a strategic surrender. [Parliament of Australia, 2004]

5. Comparative Analysis

The proposed Bangladesh agreement represents an extreme departure from historical trade and investment deals, both in scope and intensity. Unlike past agreements which typically targeted specific sectors, this deal involves an across-the-board erosion of Bangladesh’s sovereignty—affecting food safety, health regulations, digital governance, labor law, and even defense policy.

Whereas earlier agreements tended to avoid overt geopolitical signaling, this one takes a clear anti-China stance, explicitly aligning Bangladesh with U.S. strategic interests. In regulatory terms, the deal proposes a full surrender to U.S. agencies like the FDA, FSIS, USDA, and BIS—granting them overriding authority without reciprocal influence or review, something only partially seen in earlier cases.

In terms of labor law, the scale of restructuring demanded—particularly of the Bangladesh Labour Act and EPZ frameworks—is deeper than anything imposed except possibly in Mexico under USMCA. Most notably, the inclusion of mandatory U.S. defense procurement is without precedent in the history of trade agreements, marking a profound securitization of what should be economic diplomacy.

Despite these far-reaching concessions, Bangladesh is offered no guaranteed market access in return—unlike the mutual arrangements in deals like USMCA. At the same time, it is being locked into long-term energy dependence through required U.S. LNG imports, an uncommon feature in traditional trade frameworks.

Finally, the chapter on investment mirrors the most aggressive aspects of bilateral investment treaties (BITs), offering full liberalization and unrestricted investor rights, but without the developmental safeguards or mutual obligations typically built into such treaties—even those criticized for being one-sided.

In short, this is not a typical trade agreement. It represents a profound structural transformation, with Bangladesh yielding far more than any of its historical counterparts—yet receiving little to nothing in return. The only comparable moments in history are the unequal treaties imposed by colonial powers on China (Treaty of Nanking, etc.) or the East India Company’s resource control treaties with Mughal successors.

This is one of the most one-sided bilateral “trade” agreements the U.S. has attempted anywhere in the world.

6. The Moral Stakes for Our Generation

This is a Rubicon moment.

If this agreement is allowed to pass silently, it will set a dangerous precedent—not just for Bangladesh, but for every Global South country navigating the shifting tectonics of U.S.-China rivalry.

It will tell the world that:

- Regime change works.

- Interim governments can permanently surrender national interests.

- Sovereignty is tradable—if the right superpower is at the other end of the table.

That’s why silence is complicity.

7. Way Forward: The Activist Imperative

This agreement must be read not only as a trade deal but as a sovereignty-defining instrument. Its implications go beyond tariffs and customs to strike at the heart of Bangladesh’s political and economic independence. Given the lack of parliamentary oversight and public consultation, resistance is not only justified—it is imperative.

Activists, civil society organizations, and trade unions must:

- Demand full publication and translation of the agreement for public scrutiny

- Push for parliamentary debate and an independent impact assessment

- Mobilize digital and street campaigns to raise awareness and build coalitions

- Strategically link this agreement to broader global struggles against economic neocolonialism International solidarity will also be key. Global South actors must jointly challenge the normative frameworks that allow such unequal agreements to flourish under the rhetoric of “reciprocity.”

8. Conclusion: Not a Trade Agreement, But a Strategic Surrender

The so-called “US-Bangladesh Agreement on Reciprocal Trade” is, in effect, a blueprint for economic reengineering of a sovereign state—one that strips Bangladesh of its regulatory, digital, food, labor, and defense autonomy in service of an externally driven agenda.

At first glance, the agreement appears comprehensive. But that comprehensiveness is precisely the problem: there is no sphere of domestic policy it does not touch, and no clause in which Bangladesh secures equivalent concessions from the United States. From pharmaceuticals to fisheries, encryption to energy, the document cements a subordinate role for Bangladesh in a global system designed to serve the political and commercial interests of the United States.

When placed beside other asymmetrical trade deals—from NAFTA’s strain on Mexican agriculture, to Colombia’s regulatory losses, to Africa’s surrender of policy space through BITs—this agreement stands out for its sheer audacity and totality. Rarely has a Global South country been asked to concede so much—without war, debt default, or natural disaster as the trigger.

Instead, what makes this agreement even more disturbing is its context: it emerges at a moment when Bangladesh is without an elected government, led by an interim regime with contested legitimacy, and reeling from orchestrated social unrest. In such conditions, a treaty of this magnitude amounts not to negotiation—but to submission.

Let us be clear: this is not about trade. It is about:

- Embedding U.S. corporate dominance in food, health, and energy sectors;

- Exporting U.S. digital and surveillance norms under the guise of cybersecurity;

- Securing military and strategic alignment against China;

- And institutionalizing neoliberal discipline in Bangladeshi labor and governance systems.

There is no vision here for Bangladesh’s industrialization, no protection for infant industries, no meaningful pathway for equitable development. What we see instead is a manual for dependency, branded as reciprocity.

History rarely gives a country such stark choices: to either kowtow quietly into dependency, or to

stand, speak, and resist—not just for ourselves, but for generations to come.

This agreement cannot pass.

Because if it does, Bangladesh will not be trading its goods. It will be trading away its future.

It is now up to the people—not unelected regimes, not foreign investors—to decide whether such

a future is acceptable.

References

- United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA)

Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). (2020). United States–Mexico

Canada Agreement (USMCA): Full text and fact sheets. Retrieved from https://ustr.gov/trade

agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement

Congressional Research Service. (2020). USMCA: Implementation and Comparison to NAFTA

(CRS Report No. R44981). Retrieved from https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44981 - U.S.–Colombia Free Trade Agreement (2012)

Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). (2012). Colombia Trade Promotion

Agreement: Final Text. Retrieved from https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade

agreements/colombia-tpa/final-text

Human Rights Watch. (2011, April 6). Colombia: Labor Violence and the U.S. Free Trade

Agreement. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/04/06/colombia-labor-violence-and

us-free-trade-agreement - Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) with African States

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (n.d.). Investment Policy

Hub: International Investment Agreements Navigator. Retrieved

from https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements

South Centre. (2016). Bilateral Investment Treaties in Africa: A Review (Policy Brief No.

4). Retrieved from https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/IB2016-4-Bilateral

Investment-Treaties-in-Africa-EN.pdf - IMF Structural Adjustment Programs (1980s–2000s)

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (1998). Review of the Structural Adjustment

Programs. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/exrp/sasr/index.htm

World Bank. (1992). Review of Bank Support for Structural Adjustment Operations. Retrieved

from https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents

reports/documentdetail/192001468739447199/review-of-bank-support-for-structural-adjustment

operations

Structural Adjustment Participatory Review International Network (SAPRIN). (2004). The

Policy Roots of Economic Crisis and Poverty: A Multi-Country Participatory Assessment of

Structural Adjustment. Retrieved from http://www.saprin.org/SAPRIN_Findings.pdf - Australia–U.S. Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA)

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), Australia. (2005). Australia–United States

Free Trade Agreement: Official Documents. Retrieved

from https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/ausfta/official-documents

Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). (2005). Australia FTA. Retrieved

from https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/australia-fta

Parliament of Australia. (2004). Report 61: Australia–United States Free Trade Agreement

(Joint Standing Committee on Treaties). Retrieved

from https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Treaties/Completed_inq

uiries/2004/aus_usfta/report